Snail sinistrality – levotočivost plžů (Gastropoda)

Snail sinistrality – levotočivost plžů – je klíčovou složkou plžení jxd. Bilogy: „Většina plžů je stočena ve směru hodinových ručiček, avšak u některých druhů se vyskytují vzácné genetické varianty s obráceným vinutím. Nyní byl identifikován molekulární determinant směru navíjení, cytoskeletální regulátor formin.“ (Maderspacher, 2016). V impaktovaném časopise díky tomu nejde své místo i nálezová zpráva, že v Polsku byl nalezen sinistrální hlemýžď. (Szybial et all. 2015). Chiralita je zkoumána od počátků vzniku malého šneka, už před pářením. Výzkum ukázal, že předkopulační chování plovatky Lymnaea stagnalis je lateralizováno. Asymetrie chování odpovídá sinistrální nebo dextrální chiralitě jedince a je zjevně také řízena lokusem meternálního efektu. To ukazuje, že lateralizované sexuální chování L. stagnalis je od počátku vzniku jedince a je přímým důsledkem asymetrie celého těla. (Davison, et all. 2008)

Výzkum sinistrality pokryl všechny představitelné aspekty malakologického bádání. Pozorování sinistrálního vzorku Arianta arbustorum vědci prokázali, že kopulace zrcadlově převrácených (dextrální x sinistrální) jedinců je velmi komplikovaná. (Gittenberger, Margy, 2011). Pozorování pokusů o kopulaci Arianta arbustorum ukázalo, že jedinci s opačnou chiralitou se nemohou pářit úspěšně. (Margry, Gittenberger 2011). Druhy s plochými ulitami se páří „tváří v tvář“. Tato sexuální symetrie zabraňuje interchirálnímu páření, protože pohlavní orgány vystavené sinistrálem na levé straně nemohou být spojeny s těmi, které jsou vystaveny dextrálníém jedincem na pravé straně. Výhoda proti chirální menšině, která vyplývá z páření, tedy stabilizuje chirální monomorfismus. Druhy s vysokými ulitami jsou nerecipročně spojeny: „samec“ se kopuluje tím, že namontuje plášť „samice“, vzájemně se vyrovnává stejným směrem. Tato sexuální asymetrie umožňuje interchirální kopulaci jen s malými změnami chování. Proto alely reverze přetrvávají déle v populacích druhů s vysokou ulitou. (Asami, Cowie 1998).

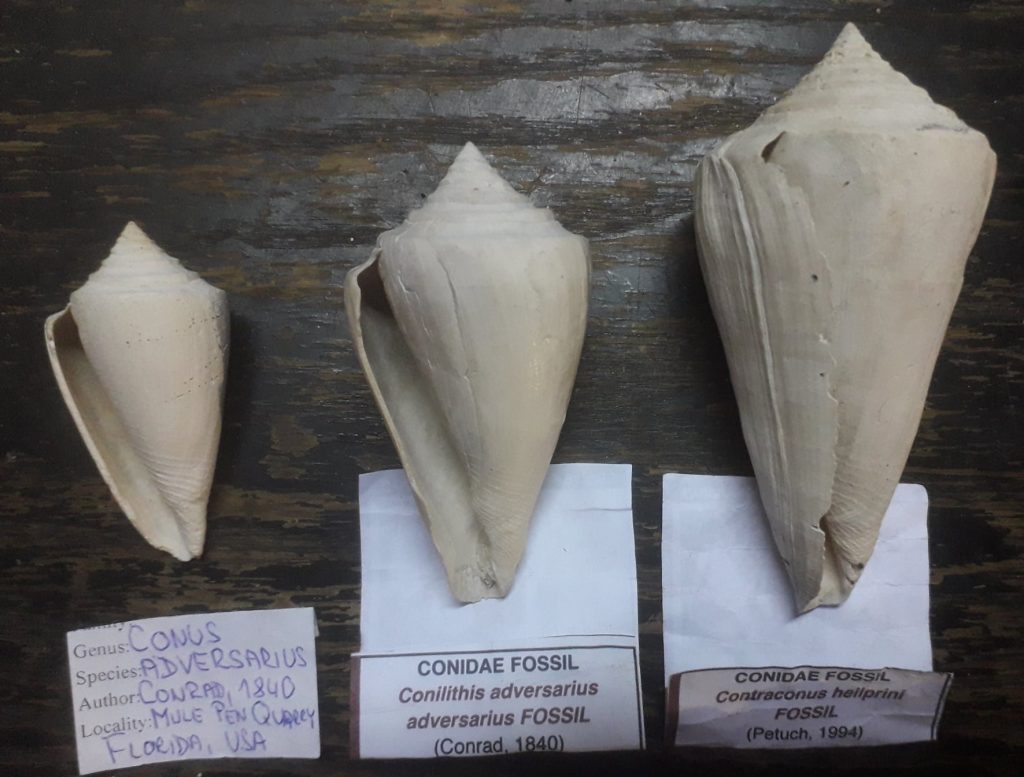

Fosilní sinistrální Conidae – homolice

O sinistralitě se uvažuje i jako o možném zdroji speciace. U několika málo druhů plžů je chiralita určována jediným genetickým lokusem se zpožděnou dědičností, genotyp se projevuje v potomcích matky. Pokusy o izolování lokusů zapojených do chirality plžů se sněží zjistit, jak symetrie vytvořena. Obyčejně se předpokládá, že silná selekce závislá na frekvenci by měla působit proti vytvoření nových chirálních typů, protože chirální menšina má potíže s nalezením vhodného párového partnera (jejich genitálie jsou na „špatné“ straně). Smíšené populace by proto neměly přetrvávat. Ale velmi málo druhů pozemských hlemýždí, zejména subgenus Amphidromus sensu stricto, se nejen zdá, že se náhodně spojí mezi různými chirálními typy, ale mají také stabilní chirální dimorfismus v rámci populace, což naznačuje zapojení vyrovnávacího faktoru. Na druhém konci spektra, u mnoha druhů, se různé chirální typy nedokáží spojit, a tak by se mohly navzájem reprodukovat. Zatímco empirické údaje, modely a simulace naznačují, že se někdy musí objevit chirální obrat, je málo pravděpodobné, že povede k takzvanému „jednogenovéu“ speciaci. Nicméně chirální zvrácení by mohlo být k speciaci (nebo k divergenci po speciaci) přispět. (Davidson, 2005). Jednorázová speciace se považuje za nepravděpodobnou, ale vyskytla se u hlemýžďů, u nichž byl gen pro pravolevou chiralitu obrácen a způsobil vznik několika nových druhů. Tato změna může být usnadněna malou velikostí populace a maternálním efektem – „opožděnou dědičností“, kdy je fenotyp jedince určován genotypem jeho matky. (Yamamichi,Sasaki 2013).

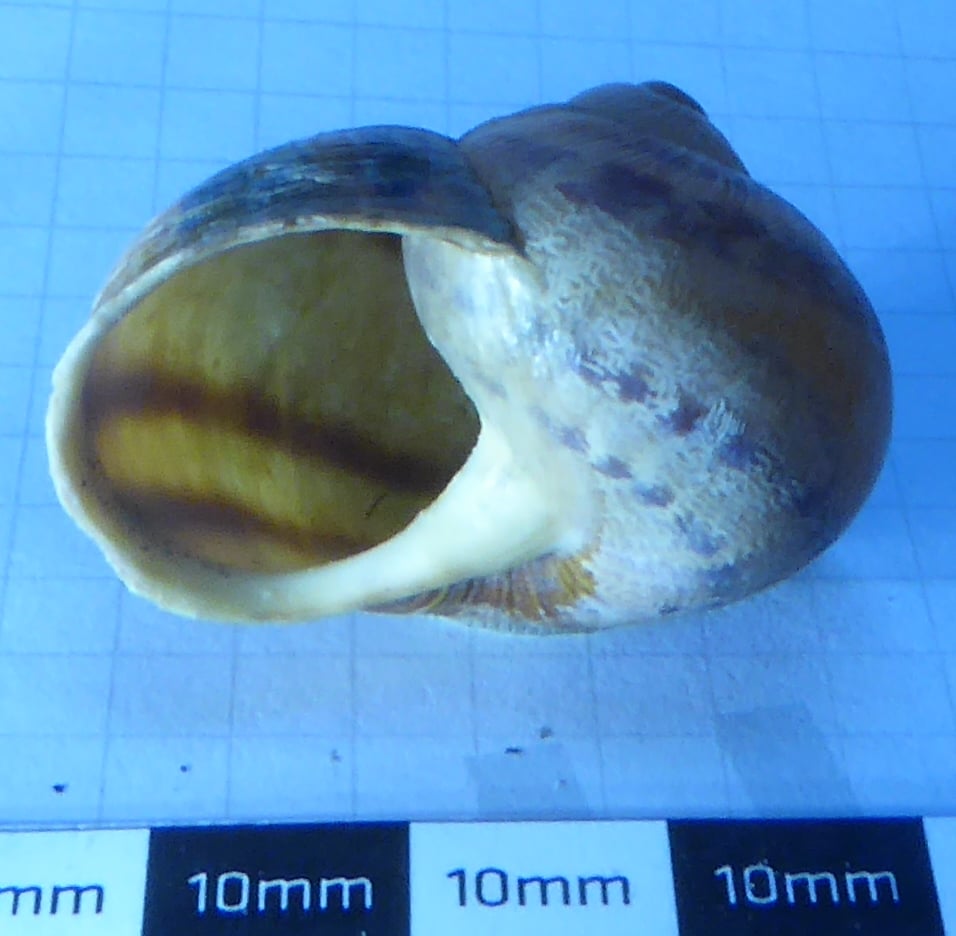

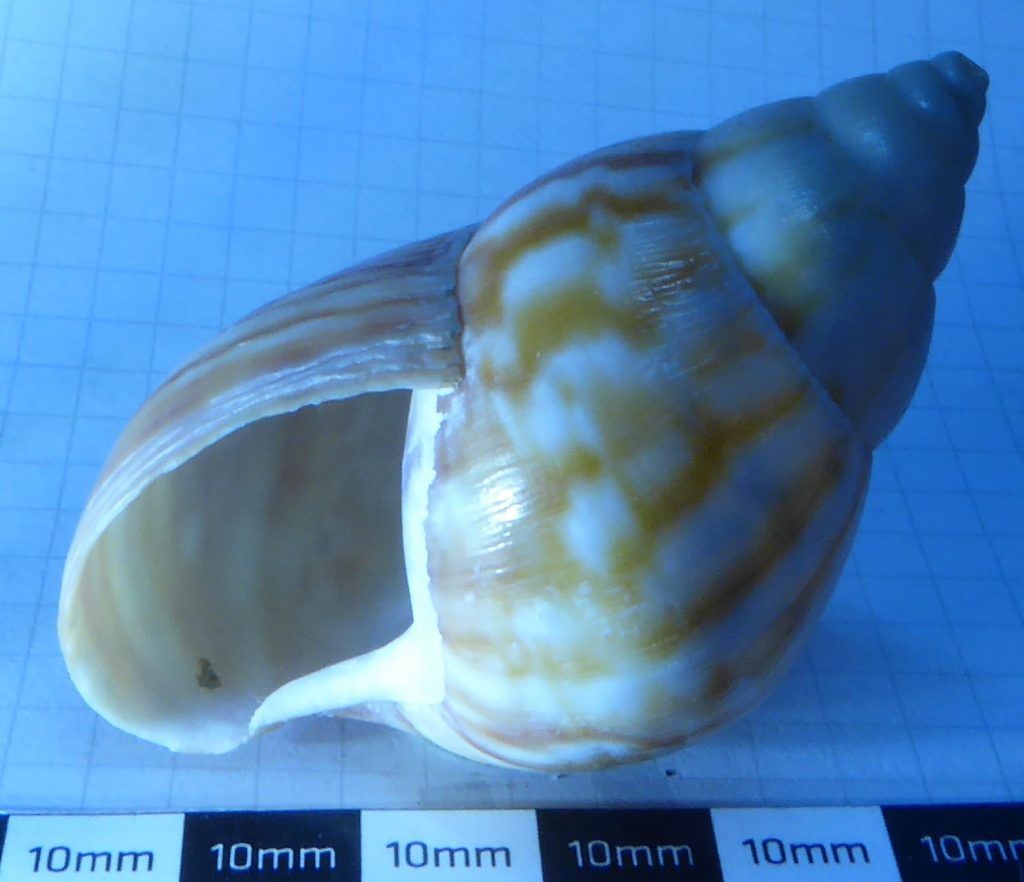

Chiralita může být starým znakem odvozeným z bilaterie. Vypnutí mutace v jedné kopii tandemově duplicitního diafanu – příbuzného forminu je dokonale spojeno se zlomem symetrie ulity plže. To je podpořeno zjištěním, že léčba anti-forminem přeměňuje embrya dextrálního šneku na sinistrální fenokopie a un žab inhibice forminu má chirality-randomizing efekt u raných (pre-cilia) embryí. V rozporu s očekáváními založenými na stávajících modelech jsme objevili asymetrickou expresi genů v embryích s hlemýžďem dvou a čtyř buněk, které předcházejí morfologické asymetrii. Vzhledem k tomu, že vlákno formin-aktinu bylo prokázáno, že je součástí inverzního přepínače asymetrie, jsou společně tyto výsledky v souladu s názorem, že zvířata s různými tělesnými plány mohou odvodit své asymetrie ze stejných intracelulárních chirálních prvků. (Davison, Angus, et all. 2016). Malý výskyt sinistrality v poměru k dextrálitě u plžů je nevysvětleno. U rodu Conus se sinistrální skořápka vyvinula jako převažující charakteristika druhu jen jednou. Fosílie tohoto druhu, Conus adversarius, se nacházejí v horním pliocenu a nejmenších pleistocénových ložiscích v jihovýchodním USA. Conus adversarius měl neplanktonický vývoj larev; to mohlo být kritickým faktorem pro včasnou speciaci, stejně jako sinistrální mořské druhy jiných clade. Většina vzorků aberantně sinistrálních recentních jedinců rodu Conus jsou odvozeny od typicky dextrálních druhů, které mají nonplanktonický vývoj. Pokud byl C. adversarius izolován reproduktivně z dextrálních konspecifických znaků, pak tento druh může poskytnout příklad téměř okamžité sympatrické speciace ve fosilním záznamu. (Hendricks, J. R. 2009).

U druhů plžů, kde jsou sinistralita i dextralita skutečně běžně přítomné, určuje směr navíjení jediný gen s opožděšnou marternální dědičností; neexistuje žádná předvídatelná souvislost mezi vlastním genotypem směru navíjení hlemýždě a jeho skutečným směrem stočení. Kvůli tomuto genetickému oddělení se dá očekávat, že dextrální a sinistrální jedinci budou přesně zrcadlovými obrazy jednoho druhého. Nicméně existují náznaky, že existuje jemný, ale zjistitelný tvarový rozdíl mezi dextrálními a sinistrálními jedinci, které pocházejí ze stejného genofondu.Při zýzkumu 50 dextrálních a 50 sinistrálních jedinců Amphidromus inversus. Když byly ulity podrobeny geometrické morfometrické analýze, sinistrální jedinci skutečně vykazovali mírné, ale významné rozšíření a zkroucení skořápky v blízkosti palatinální a parietální aperturní oblasti. (Schilthuizen, Haase 2010). Řada vědců považuje jednogenovou speciaci za reálnou. U suchozemských hlemýžďů by mohl být zodpovědný za okamžitou speciaci jediný gen pro směrování vinutí vlevo-vpravo. Experimenty ukazují, že sinistrální hlemýždi Camaenidae přežívají při predaci hady Pareas iwasakii (Colubroidea: Pareatidae) lépe než dextrální. (Hoso, et all., 2010). V provedené simulaci se diskutovala speciace na základě jednoho genu chirality. Konkrétně se zkoumalo šest faktorů, a to: (i) absolutní a relativní velikost populace; (ii) úspěch páření, o kterém je známo, že souvisí s tvarem pláště, zejména poměrem výška / šířka; (iii) vliv maternálního efektu, zákládajícím chiralitu; iv) (nízká) pohyblivost šneků; v) rozdíly v způsobilosti (heterosa); a (vi) zda invazivní mutantní alela je dominantní nebo recesivní. Dopad těchto faktorů byl kvantifikován.

Malá populace s nepatrným počtem predátorů a dominantní postavení alely mutantní chirality mají zásadní význam pro příležitostnou fixaci druhu. (van Batenburg, Gittenberger, 1996). Podle jiných autorů jsou však důkazy na podporu jednogenového speciace řídké, většinou založené na monogenních mitochondriálních studiích a vzorcích chirálních variací mezi jednotlivými druhy.

Studie použila teoretický model, který ukázal, že chirální fenotyp potomstva je určován maternálním genotypem,. Mohou se tedy objevit příležitostné chirální obraty, a umožní se tok genů mezi morfovými zrcadlovými obrazy, které brání speciaci. Empiricky se ukázalo, že mezi různými chirálními typy japonských druhů Euhadra existuje nedávný nebo probíhající genový tok. Zaznamenány byly také důkazy o spojení mezi zrcadlovými morfy, které přímo ukazují potenciál pro tok genů. Takže teoretické modely naznačují tok genů mezi opačně navinutými hlemýžďmi a empirická studie ukázaly, že se mohou spojit a že u rodu Euhadra dochází k toku genů mezi jedinci s opačným vinutím. Je zapotřebí víc než jediný gen, než může být chirální změna směru vinutí ulity považována za vytvoření nového druhu. (Richards, et all. 2018).

SNAIL SINISTRALITY

Current Bilogy: „Most snails are twisted clockwise, but some species have rare inverted winding genetic variants. A molecular determinant of coiling direction, the cytoskeletal regulator formin, has now been identified.“ (Maderspacher, 2016). As a result, the impact report that a sinister snail was found in Poland is out of place in the impact magazine. (Szybial et al. 2015). Chirality has been studied since the beginning of the formation of the small snail, even before mating. Research has shown that the precoupling behavior of Lymnaea stagnalis is lateralized. Behavioral asymmetry corresponds to the sinistral or dextral chirality of an individual and is apparently also controlled by the locus of the meternal effect. This indicates that the lateralized sexual behavior of L. stagnalis is from the beginning of the individual’s origin and is a direct consequence of the asymmetry of the whole body. (Davison, et al. 2008).

Sinistrality research covered all imaginable aspects of malacological research. Observations of a sinistral sample of Arianta arbustorum have shown that the coupling of mirror-inverted (dextral x sinistral) individuals is very complicated. (Gittenberger, Margy, 2011). Observations of attempts to couple Arianta arbustorum have shown that individuals with opposite chirality cannot mate successfully. (Margry, Gittenberger 2011). Species with flat shells mate „face to face“. This sexual symmetry prevents interchiral mating because the genitals exposed by the sinister on the left side cannot be associated with those exposed by the dexteral individual on the right side. Thus, the advantage over the chiral minority that results from mating stabilizes the chiral monomorphism. Species with tall shells are non-reciprocally connected: the „male“ copulates by fitting the mantle of the „female“, aligning each other in the same direction. This sexual asymmetry allows interchiral coupling with only small changes in behavior. Therefore, reversal alleles persist longer in populations of high shell species. (Asami, Cowie 1998).

Sinistrality is also considered as a possible source of speciation. In a few species of snails, chirality is determined by a single genetic locus with delayed inheritance, the genotype is manifested in the offspring of the mother. Attempts to isolate the loci involved in the chirality of snails are snowing down to see how the symmetry is created. It is generally assumed that strong frequency-dependent selection should counteract the formation of new chiral types, as the chiral minority has difficulty finding a suitable pairing partner (their genitals are on the „wrong“ side). Mixed populations should therefore not persist. But very few terrestrial snail species, especially the subgenus Amphidromus sensu stricto, not only appear to coincide randomly between different chiral types, but also have stable chiral dimorphism within the population, suggesting the involvement of a balancing factor. At the other end of the spectrum, in many species, different chiral types cannot combine and could reproduce each other. While empirical data, models, and simulations suggest that a chiral turn must sometimes occur, it is unlikely to lead to so-called „single-gene“ speciation. However, chiral perversion could contribute to speciation (or divergence after speciation). (Davidson, 2005). A single speciation is considered unlikely, but has occurred in snails in which the right-left chirality gene has been reversed to create several new species. This change may be facilitated by the small size of the population and the maternal effect – „delayed inheritance“, where the phenotype of an individual is determined by the genotype of his mother (Yamamichi, Sasaki 2013).

hanges in the direction of the shell winding are considered by some scientists to be a strange immediate case of speciation. The sudden reproductive isolation between parents and offspring of various conch shells is complicated and deserves to be studied mathematically. (Gittenberger, 1988). The evolutionary advantage of chirality is investigated. The study showed that fossil dextral snails resisted the attacks (right-attacking) of crabs much better than sinister snails, yet dextrality is fully prevalent in snails. (Dietl, Hendricks, 2006) In nature, 90 percent of snail taxa are dextral. (Davidson. 2005). The focus is, of course, on the mechanism of forming the winding direction itself. In many cases, chirality is affected by cytoskeletal actin dynamics. Although it is well known that the actin cytoskeleton generates rotational forces at the molecular level, we are only beginning to understand how this can lead to the chiral behavior of the entire actin network in vivo. Chiral cell division can be achieved by properly adapting the molecular dimensioning torque generation processes in the actomyosin cytoskeleton.

Chirality may be an old sign derived from bilateralism. Turning off the mutation in one copy of the tandem duplicate diaphane-related formin is perfectly associated with a break in the symmetry of the snail shell. This is supported by the finding that anti-formin treatment converts dextral snail embryos to sinistral phenocopies, and that frog inhibition of formin has a chirality-randomizing effect in early (pre-cilia) embryos. Contrary to expectations based on existing models, we found asymmetric gene expression in two- and four-cell snail embryos that preceded morphological asymmetry. Because the formin-actin fiber has been shown to be part of the inverse switch of asymmetry, these results are consistent with the view that animals with different body plans can derive their asymmetries from the same intracellular chiral elements. (Davison, Angus, et al. 2016). The small incidence of sinistrality relative to dextrality in snails is unexplained. In the genus Conus, the sinistral shell developed as the predominant characteristic of the species only once. Fossils of this species, Conus adversarius, are found in the Upper Pliocene and the smallest Pleistocene deposits in the southeastern United States. Conus adversarius had nonplanktonic larval development; it could be a critical factor for early speciation, as well as sinister marine species of other clades. Most samples of aberrantly sinistral recent individuals of the genus Conus are derived from typically dextral species that have nonplanktonic development. If C. adversarius has been isolated reproducibly from dextral conspecific traits, then this species can provide an example of almost immediate sympatric speciation in the fossil record. (Hendricks, J. R. 2009).

The direction of winding of pulmonary snails is determined by a single gene through the maternal effect, which causes the cytoskeletal dynamics in the early embryo of dextral snails to be a mirror image of a sinister individual. The spermatids of pulmonary snails undergo a spiral twist during development. The direction of coiling of the helical elements of spermatozoa is also likely to affect the behavior of the female reproductive tract, leading to the possibility that chiral sperm function plays a role in maintaining whole-body chiral dimorphism in tropical tree Amphidromus inversus (Muiller, 1774). Sperm in A. inversus are always dextrally wound, regardless of the direction of winding of the animal itself. Schilthuizen, van Heuven, 2011). Recent advances in research into the asymmetry of animal development and their chirality have revealed new mechanisms underlying the development of invertebrate chirality. The findings in Drosophila and snails suggest that the actin filament-dependent mechanism may be evolutionarily conserved by protostomy. Preservation of the primary asymmetry of polarity across most metazoan phyla, which represents a visceral ability, indicates developmental limitations and purification of selection as possible but unexplored mechanisms. (Takashi et al., 2008). For more than a hundred years, it has been commonly assumed that the mirror image of the shell of snails is fully correlated with the inverted mirror image of spindle orientation and fission. The results now refute this model, showing that sinistrality may not be a mirror image of dextrality. (Wandelt, 2004). However, the predominance of one species of asymmetry over another in recent snail taxa contrasts with approximately the same number of sinistral and dextral populations of fossil nautiloid and ammonoid cephalopods. (Vermeij, 1975). The study combines intraciliary calcium oscillations with target motility and a subsequent cascade of signaling nodes that control left-hand orientation (Blum, Phillip 2015).

The direction of winding of pulmonary snails is determined by a single gene through the maternal effect, which causes the cytoskeletal dynamics in the early embryo of dextral snails to be a mirror image of a sinister individual. The spermatids of pulmonary snails undergo a spiral twist during development. The direction of coiling of the helical elements of spermatozoa is also likely to affect the behavior of the female reproductive tract, leading to the possibility that chiral sperm function plays a role in maintaining whole-body chiral dimorphism in tropical tree Amphidromus inversus (Muiller, 1774). Sperm in A. inversus are always dextrally wound, regardless of the direction of winding of the animal itself. Schilthuizen, van Heuven, 2011). Recent advances in research into the asymmetry of animal development and their chirality have revealed new mechanisms underlying the development of invertebrate chirality. The findings in Drosophila and snails suggest that the actin filament-dependent mechanism may be evolutionarily conserved by protostomy. Preservation of the primary asymmetry of polarity across most metazoan phyla, which represents a visceral ability, indicates developmental limitations and purification of selection as possible but unexplored mechanisms. (Takashi et al., 2008). For more than a hundred years, it has been commonly assumed that the mirror image of the shell of snails is fully correlated with the inverted mirror image of spindle orientation and fission. The results now refute this model, showing that sinistrality may not be a mirror image of dextrality. (Wandelt, 2004). However, the predominance of one species of asymmetry over another in recent snail taxa contrasts with approximately the same number of sinistral and dextral populations of fossil nautiloid and ammonoid cephalopods. (Vermeij, 1975). The study combines intraciliary calcium oscillations with target motility and a subsequent cascade of signaling nodes that control left-hand orientation (Blum, Phillip 2015).

In snail species, where both sinistrality and dextrality are indeed commonly present, the direction of coiling is determined by a single gene with delayed marteral inheritance; there is no predictable link between the actual genotype of the coil winding direction and its actual twisting direction. Due to this genetic separation, dextral and sinistral individuals can be expected to be exactly mirror images of each other. However, there are indications that there is a subtle but detectable difference in shape between dextral and sinistral individuals that come from the same gene pool. In research, 50 dextral and 50 sinistral individuals of Amphidromus inversus. When the shells were subjected to geometric morphometric analysis, the sinistral individuals actually showed a slight but significant expansion and twisting of the shell near the palatal and parietal aperture areas. (Schilthuizen, Haase 2010). Many scientists consider single-gene speciation to be real. In terrestrial snails, a single left-right winding gene could be responsible for immediate speciation. Experiments show that sinistral snails Camaenidae survive better than dextral snakes during predation by Pareas iwasakii (Colubroidea: Pareatidae). (Hoso, et al., 2010). In the performed simulation, speciation based on one chirality gene was discussed. Specifically, six factors were examined, namely: (i) absolute and relative population size; (ii) mating success, which is known to be related to the shape of the shell, in particular the height / width ratio; (iii) the effect of the maternal effect establishing chirality; (iv) (low) auger mobility; (v) differences in eligibility (heterosis); and (vi) whether the invasive mutant allele is dominant or recessive. The impact of these factors has been quantified. A small population with a small number of predators and a dominant position of the mutant chirality allele are essential for the occasional fixation of the species. (van Batenburg, Gittenberger, 1996). However, according to other authors, evidence to support single gene speciation is sparse, mostly based on monogenic mitochondrial studies and patterns of chiral variation between species. The study used a theoretical model that showed that the chiral phenotype of the offspring is determined by the maternal genotype. Thus, occasional chiral turns may occur, and genes may flow between morphic mirror images that prevent speciation. Empirically, it has been shown that there is a recent or ongoing gene flow between different chiral types of Japanese Euhadra species. Evidence of a link between mirror morphs has also been reported, directly indicating the potential for gene flow. Thus, theoretical models suggest gene flow between oppositely wound snails, and empirical studies have shown that they can coalesce and that in the genus Euhadra, gene flow occurs between individuals with opposite windings. More than a single gene is needed before a chiral change in the direction of the shell winding can be considered a new species. (Richards, et al. 2018).

In snail species, where both sinistrality and dextrality are indeed commonly present, the direction of coiling is determined by a single gene with delayed marteral inheritance; there is no predictable link between the actual genotype of the coil winding direction and its actual twisting direction. Due to this genetic separation, dextral and sinistral individuals can be expected to be exactly mirror images of each other. However, there are indications that there is a subtle but detectable difference in shape between dextral and sinistral individuals that come from the same gene pool. In research, 50 dextral and 50 sinistral individuals of Amphidromus inversus. When the shells were subjected to geometric morphometric analysis, the sinistral individuals actually showed a slight but significant expansion and twisting of the shell near the palatal and parietal aperture areas. (Schilthuizen, Haase 2010). Many scientists consider single-gene speciation to be real. In terrestrial snails, a single left-right winding gene could be responsible for immediate speciation. Experiments show that sinistral snails Camaenidae survive better than dextral snakes during predation by Pareas iwasakii (Colubroidea: Pareatidae). (Hoso, et al., 2010). In the performed simulation, speciation based on one chirality gene was discussed. Specifically, six factors were examined, namely: (i) absolute and relative population size; (ii) mating success, which is known to be related to the shape of the shell, in particular the height / width ratio; (iii) the effect of the maternal effect establishing chirality; (iv) (low) auger mobility; (v) differences in eligibility (heterosis); and (vi) whether the invasive mutant allele is dominant or recessive. The impact of these factors has been quantified. A small population with a small number of predators and a dominant position of the mutant chirality allele are essential for the occasional fixation of the species. (van Batenburg, Gittenberger, 1996). However, according to other authors, evidence to support single gene speciation is sparse, mostly based on monogenic mitochondrial studies and patterns of chiral variation between species. The study used a theoretical model that showed that the chiral phenotype of the offspring is determined by the maternal genotype. Thus, occasional chiral turns may occur, and genes may flow between morphic mirror images that prevent speciation. Empirically, it has been shown that there is a recent or ongoing gene flow between different chiral types of Japanese Euhadra species. Evidence of a link between mirror morphs has also been reported, directly indicating the potential for gene flow. Thus, theoretical models suggest gene flow between oppositely wound snails, and empirical studies have shown that they can coalesce and that in the genus Euhadra, gene flow occurs between individuals with opposite windings. More than a single gene is needed before a chiral change in the direction of the shell winding can be considered a new species. (Richards, et al. 2018).

Literatura:

Asami, Takahiro, Cowie, Robert H. (1998).Evolution of Mirror Images by Sexually Asymmetric Mating Behavior in Hermaphroditic Snails. The American Naturalist 1998. DOI: 10.1086/286163

Blum, Martin., Vick, Phillip (2015). Left–Right Asymmetry: Cilia and Calcium Revisited. Journal for Current Biology. Vol. 25, Iss.5, 2015, pp. R205-R207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.031

Čevela, Vlastimil (2018). Osobní sdělení majitele zemědělské farmy Farma Nahošovice zabývající se velkochovem kaviárových hlemýžďů Helix aspersa. (Farma Nahošovice, Nahošovice č.p. 25, Dřevohostice, Czech Republic) dne 11. prosince 2018.

Davison, Angus, Schilthuizen, Menno, (2005). The convoluted evolution of snail chirality. The Science of Nature. DOI: 10.1007/s00114-05-0045-2

Davison, Angus, Frend, Hayley T., Moray, Camile, Wheatley, Hannah, Searle, Laura J. and Eichhorn, Markus P. (2008): Mating behaviour in Lymnaea stagnalis pond snails is a maternally inherited, lateralized trait. Biology Letters: Animal behaviour. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2008.0528

Davison, Angus., McDowell,Gary S., Holden, Jennifer M., Johnson, Harriet F., Koutsovoulos, Georgios D., Liu, M. Maureen., Hulpiau, Paco., Van Roy, Frans., Wade, Christopher M., Banerjee, Ruby., Yang, Fengtang., Chiba, Satoshi., Davey,John W., Jackson, Daniel J., Levin, Michael and Blaxter, Mark L.(2016). Formin Is Associated with Left-Right Asymmetry in the Pond Snail and the Frog. Current Biology. Vol. 26, Iss. 5, pp. 654-660, MARCH 07, 2016.Online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26923788/

Dietl, Gregory P,. Hendricks, Jonathan R. (2006). Crab scars reveal survival advantage of left-handed snails. Biol Lett. 2006 Sep 22; 2(3): 439–442. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0465

Gittenberger, Edmund (1988). Notes and commnets sympatric speciation in snails; a largely neglected model. Evolution, 42(4), 1988, pp. 826-828

Gittenberger, E., Margy, C.J.P.J.(2011). Premating isolation reconfirmed in Arianta arbustorum (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Helicidae). Basteria, vol. 75 (4-6), 2011, 57-58. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317239100_Premating_isolation_reconfirmed_in_Arianta_arbustorum_Linnaeus_1758_Gastropoda_Pulmonata_Helicidae

Haase, Martin, Baur, Bruno (1995). Variation in spermathecal morphology and storage of spermatozoa in the simultaneously hermaphroditic land snail Arianta arbustorum (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Stylommatophora). Invertebrate Reproduction & Development 33.Vol. 28. Iss. 1. DOI: 10.1080/07924259.1995.9672461

Hendricks, J. R. (2009), Sinistral snail shells in the sea: developmental causes and consequences. Lethaia. Vol. 42. pp. 55-66. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2008.00103.x

Hoso,Masaki., Kameda,Yuichi,. Wu,Shu-Ping., Asami,Takahiro., Kato,Makoto, and Hori, Michio (2010).A speciation gene for left–right reversal in snails results in anti-predator adaptation. Nature Communications. 2010. Vol. 1. pp. 133. doi:10.1038/ncomms1133

Maderspacher, Florian (2016). Snail Chirality: The Unwinding. Current Biology Dispatches https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(16)30060-4.pdf

Margry, C.J.P.J., Gittenberger E.(2011). Premating isolation reconfirmed in Arianta arbustorum (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Helicidae). Basteria. Vol. 75 (4-6).

Naganathan, Sundar Ram, Middelkoop,Teije C., Fürthauer, Sebastian, Grill, Stephan W. (2016).Actomyosin-driven left-right asymmetry: from molecular torques to chiral self organization. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2016.01.004

Nakadera, Yumi, Blom, Christiaan, Koene, Joris M. (2014). Duration of sperm storage in the simultaneous hermaphrodite Lymnaea stagnalis Journal of Molluscan Studies, Volume 80, Issue 1, pp. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyt049

Richards,Paul M., Morii,Yuta., Kimura,Kazuki., Hirano,Takahiro., Chiba,Satoshi and Davison, Angus (2018). Single-gene speciation: Mating and gene flow between mirror-image snails. Evolution Letterrs, Volume 2, Issue 1, Pages: 1-48, February 2018

Schilthuizen, M., Haase, M. (2010). Disentangling true shape differences and experimenter bias: are dextral and sinistral snail shells exact mirror images? Journal Zool.Vol. 282(3). pp. 191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00729.x

Schilthuizen, Menno., van Heuven, Bertie-Joan (2011). Dextral and sinistral Amphidromus inversus (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Camaenidae) produce dextral sperm. Zoomorphology. Vol. 130, p. 283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-011-0140-1

Szybiak, Krystyna, Błoszyk, Jerzy, Kalinowski, Tomasz, Książkiewicz, Zofia. (2015). New data on sinistral and scalariform shells among roman snail Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758 in Poland. Folia Malacologica Vol. 23: pp. 47-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.12657/folmal.023.004

Takashi Okumura,Takashi., Utsuno, Hiroki., Kuroda,Junpedi., Gittenberger, Edmund., Asami, Takahiro and Matsuno, Kenji(2008). The Development and Evolution of Left-Right Asymmetry in Invertebrates: Lessons From Drosophila and Snails. Developmental Dynamics, Vol. 237, pp. 3497–3515.

van Batenburg, F. H. D., Gittenberger, E. (1996). Ease of fixation of a change in coiling: computer experiments on chirality in snails. Heredity. 1996. Vol. 76, pp. 278. The Genetical Society of Great Britain. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/hdy.1996.41

Vermeij, Geerat J. (1975).Evolution and distribution of left-handed and planispiral coiling in snails. Nature. Nature Publishing Group. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/254419a0

Wandelt, J., Nagy, L.M. (2004). Left-Right Asymmetry: More Than One Way to Coil a Shell. Current Biology. Volume 14, Issue 16, 2004, Pp. R654-R656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.010

Whelan, Nathan V., Strong, Ellen E. (2014). Seasonal reproductive anatomy and sperm storage in pleurocerid gastropods(Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae). Can. J. Zool. 92: 989–995 (2014) dx.doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2014-0165

Yamamichi, Masato., Sasaki, Akira (2013). SINGLE-GENE SPECIATION WITH PLEIOTROPY: EFFECTS OF ALLELE DOMINANCE, POPULATION SIZE, AND DELAYED INHERITANCE. Evolution. The Society for the Study of Evolution. Evolution 67-7: 2011–2023. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/evo.12068